Prime Minister Modi’s

comment (see here)

that the UPA government left the government coffers empty for the NDA

government predictably drew a strong response from the former Finance Minister,

P.C. Chidambaram (here).

The context for the controversy was that the fiscal deficit for the first two

months of the fiscal year 2014-15 had reached 45% of the budget estimates. Some

commentators – example: Madan Sabnavis of CARE Ratings – also felt that the UPA

government had used up an excessive amount of the budgeted fiscal deficit in

the first two months of the fiscal year 2014-15 (here).

A question that arises

here is whether a government, certain of defeat in an election, strategically

leaves its successor government with a high deficit in order to constrain its manoeuvrability

(See Hodler).

If such strategic behaviour has, in fact, taken place, how can we find evidence

for it? What we need to examine is whether the outgoing UPA government spent

recklessly during April and May of 2014. More importantly, did it do this

knowing fully well that it would be defeated and wished to deliberately leave government

finances in a poor state for the incoming NDA government? I seek to answer

these questions by comparing government finances during April and May of 2014

with the finances during April and May in previous years. If the finances

during April and May 2014 are significantly worse than in earlier years, we

could entertain the suspicion of reckless behaviour by the UPA government.

However, we should not

rush into any judgement of reckless behaviour. It could well be the case that

the time profile of revenue generation (via taxes, for example) and expenditure

requirements are inherently mismatched. If this is, indeed, the case, there

could well be significant gaps between expenditures and revenues (leading to

deficits) in the early months of the year while revenues catch up with

expenditures as the fiscal year rolls on.

I investigate these

issues by looking at detailed fiscal data on a monthly/quarterly basis from the

year 2003-04 (such data are not available for earlier years) till the first two

months of fiscal year 2014-15. All data

used in this note are sourced from the Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

Figure 1 gives

information on the government’s Revenue Expenditures (RE) (note below Figure 1

explains this term) incurred during the first two months of each fiscal year of

the time-period under consideration as well as Revenue Receipts (RR) generated over

the same two months of each fiscal year. This information is reported, not in terms

of actual expenditures or receipts, but as percent of announced Budget

Estimates (BE) for the fiscal year. For instance, RE is defined as:

Revenue Receipts are

defined in an analogous manner.

It is clear from the

figure that, in April and May of each fiscal year, expenditures are much

greater than receipts. It is also seen that this gap is increasing over the

years indicating that governments are increasingly front-loading expenditures

to the beginning of the year. The main reason for the gap between expenditures

and revenues is that the government’s expenditure commitments begin as soon as

the fiscal year commences but revenues (especially tax revenues) begin to flow into

government coffers much later.

Does the mismatch

between revenue expenditures and revenue receipts disappear as the fiscal year

progresses? Figure 2 shows the position for the second quarter (July –

September) for the fiscal years 2003-04 to 2013-14. RE is once again measured in

a manner similar to what was done for Figure 1 above.

Figure 2 is

dramatically different from Figure 1: the line for revenue receipts lies almost

completely above the line for revenue expenditures. It may be recalled that the

situation was the exact opposite in Figure 1. This shows that, as the year

progresses, revenues start flowing into government coffers and the mismatch

between expenditures and revenues observed in the earlier part of the year gets

rectified.

My analysis so far

seems to suggest that the behaviour of expenditures and receipts during April

and May 2014 (under the outgoing UPA government) has not been any different

from the behaviour of these two items during April and May of earlier years. Having

looked at RE and RR, I now turn my attention to Revenue Deficits.

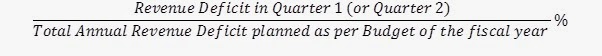

Revenue Deficits (RD) are

defined as revenue expenditure (RE) minus revenue receipts (RR). As per Indian definitions, when RE is greater

than RR there is a deficit and RD is a positive value; when RE is less than RR there

is a surplus and RD is a negative value. If RE is greater than RR, then the

government must borrow funds to meet its expenditure requirements. The data

that we use is quarterly (three month period) and extends only up to 2013-14

since RD data for April and May of 2014 were not available. Figure 3 shows RD

for Quarter 1 and Quarter 2 for each year under consideration. RD is measured

as:

As would be expected

from what we have seen in Figures 1 and 2, RD is much higher in Quarter 1 (Q1),

namely April, May and June, as compared to Q2. In Q1, due to the paucity of

revenues, RD is much higher leading to high borrowing requirements. However, in

Q2 as revenues start flowing in, RD falls, leading to much lower borrowing

requirements. Once again, the analysis does not seem to suggest any reckless

behaviour on the part of the outgoing government: borrowing requirements (due

to RE being greater than RR) have always been higher in Q1 as compared to Q2.

Having examined RD, I finally turn to Gross Fiscal Deficits (GFD) which began

the whole brouhaha about empty government coffers.

The difference between

RD and GFD is that the former considers only revenue expenditures while GFD considers

revenue and capital expenditures.

Hence, GFD is the broadest measure of the borrowing requirements of the

government and encompasses RD. The announcement that the outgoing UPA

government had used up more than 45% of the budgeted GFD during April and May

of 2014 led to much criticism that the UPA had behaved irresponsibly and had

deliberately left government finances in bad shape. The analysis so far has

suggested that there was probably nothing sinister at work on the part of the

UPA government and that such mismatch between expenditure requirements and

revenue generation at the beginning of the fiscal year has been common in

India. Figure 4 gives the profile of GFD for April & May and for Quarter 2

for each year in our dataset. GDF in the figure is measured as follows:

The figure reveals that,

generally, GFD as percentage of budget estimates in the first couple of months

is higher than what it is in Q2. The need for borrowing, as shown by GFD, falls

during Q2 as tax revenues begin to flow into government coffers. The UPA using

up 45.6% of the budgeted GFD during April and May of 2014 is, in fact, not

exceptional. This percentage was higher in 2006-07 (48.5%) and in 2008-09 (54.9%).

The analysis in this

note suggests that passing judgment on the finances of the government on the

basis of data of the first two months of a fiscal year is hasty and premature.

This is not to suggest that government finances as inherited by the NDA

government are in fine order. Clearly, the finances are in a critical state and

this fact has been recognised by the current and previous governments. The limited

point I am making is that dependence on borrowings in the first quarter (or

first couple of months) of the fiscal year is inevitable since taxes and other

revenues begin to flow to the government later in the fiscal year but expenditures

have to be incurred right from the beginning of the year. Prime Minister Modi’s

allegation regarding empty government coffers was probably an exaggeration,

designed to convey the message that government finances are not in a healthy

state and that the fiscal room available to his Finance Minister is quite

limited.

Does an outgoing

government in India behave strategically and leave its successor with less

fiscal room by running up high deficits? Do the fiscal data point to any such

election effect? In the time period under consideration, there have been three

elections and two changes of government. Both changes of government were

similar in that the outgoing government continued to rule for the first two

months of the fiscal year before the new government took over. Focusing on these

two changes in government, the analysis in this note has shown that the data during

April and May of these two years have not behaved particularly differently as

compared to April and May of non-election years. However, reaching an

empirically sound verdict on strategic behaviour of an outgoing government will

probably require more data which include more numerous changes of government. Given

the limited data that are available at this point, it is not possible to

discern any such strategic behaviour on the part of an outgoing government.