In a recent interview on 10 June 2022[i] with Karan

Thapar, the former Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India, Krishnamurthy

Subramanian strongly defended the performance of the government. It was a

wide-ranging interview, and I am not going to comment on all the issues that

were discussed. I will confine myself to just one, namely, inflation.

Inflation

Subramanian accepted that Indian inflation was

high but pointed out that it is important to compare India’s inflation

performance with that of the US and Europe. If this comparison is carried out,

it will be seen that India was not doing too badly. The gist of his argument

was that India’s average inflation over the long run (from 1960 till date) was

7.5% per annum, while the current rate of inflation is at 7.8%, which,

according to Subramanian, is just 4% higher than the long-term average. For the

US, the current rate of inflation is 8.5% compared to an average of 2%,[ii] which

according to Subramanian, is 400% higher than the long-run average. It is a

minor matter that it is 325% higher, but we can ignore that.

Subramanian did not clarify which inflation

rate he had in mind – was it CPI inflation, WPI inflation, or inflation based

on the GDP deflator? Till February 2011, India measured its inflation based on

the WPI,[iii] after which India started to measure

inflation using CPI for urban and rural areas and a combined CPI. Before 2011,

India used to measure CPI for industrial and agricultural workers. Subramanian

also did not clarify why he used the average inflation rate from 1960 onwards.

I look at the inflation using the CPI, WPI and

the GDP deflator in my computations. The source of my data is the World Bank

Indicators.[iv] My reason for

doing so is that the database reports the data on a consistent base, and I

don’t have to worry about changing the bases to get a consistent time series of

the CPI.

I first

look at CPI inflation for India, USA and Euro area for varying time periods.

Nowhere in Figure 1 do we find the average

inflation rate for the USA at 2% except in the period 2000 onwards. But in that

period, India’s inflation was 6.1%, much less than the 7.5% assumed by

Subramanian.

So, how

much higher is India’s and USA’s current inflation rate compared to their

long-run averages (as reported in Figure 1 above)? Subramanian said that

India’s current inflation rate is 4% higher than its long-run average while

that of the US is 400% higher. Let me take India’s current inflation rate at

7.8% and US’s at 8.5%, and compare it to each country’s long-run average.

Despite the difference in numbers, Subramanian is correct in spirit – the percentage difference between the current rate of inflation and the long-run average rate is much higher for the USA than it is for India for each of the time periods that we have considered.

Let us see

if this changes if I use the WPI and the GDP deflator to estimate the inflation

rate. I compute the rates of inflation using a trend equation. The US does not

report WPI inflation, which is absent in Figure 3.

By and large, the story remains the same: the

percentage difference between the current inflation rate and the long-run

average rate remains higher for the USA than for India. The numbers don’t match

with those aggressively put forward by Subramanian. This discrepancy in numbers

is disappointing especially bearing in how scathing he was in his criticism of

CMIE data on unemployment.

Apart from the data, the more critical question

that should be asked is if we should be happy that the USA’s inflation rate is

higher than its long-run average by a margin substantially greater than it is

for India. Is it a matter of satisfaction that the US is doing worse even if

India’s inflation is high? Would an Indian consumer enjoy a feeling of schadenfreude from

knowing that the average US consumer is much worse off? This

cartoon by Cartoonist Alok (@caricatured) answers these questions much better:

Economic Situation in the US and India

The other problem with Subramanian’s comparison

of the Indian and USA inflation rates is that he does not seem to compare the

prevailing economic situation in the two countries. The US economy is currently

operating very close to its potential level of Real GDP, a situation when high

inflation is likely to be a problem. As Bordoloi et al (2009)[v] note that “potential

output is the maximum output an economy could produce without putting pressure

on the price level. It is that level of output at which the aggregate demand and

supply in the economy are balanced”. They further point out that “When the

actual output exceeds the potential output, i.e. the output gap becomes

positive, the rising demand leads to an increase in the price level…Such

instances are seen as a source for inflationary pressures and as a signal for

the central bank to tighten monetary policy”. Figure 4 below shows the output

gap measured as

Output Gap (%) = [(Real GDP-Potential Real

GDP)/(Potential Real GDP)]*100

The horizontal line at 0.00 is where the two

measures of GDP are equal. The figure shows that the US economy is operating

very close to its potential output level, possibly leading to rising inflation.

The low

unemployment rate in the US economy is a concomitant of this narrowing of the

output gap. In July 2022, against all expectations, the US added 580,000 jobs

pushing the unemployment rate down to a half-century low.[vi]

India does not report real potential GDP on a

regular basis, but the RBI’s Report on Currency and Finance states that “…during the pandemic

period, a negative output gap of about 4-6 per cent per quarter during

Q2:2020-21 through Q1:2021-22 opened up” (page 18). [vii] These

estimates were reported over a year back and it is not known how much of the

negative output gap has been bridged and whether this is leading to high

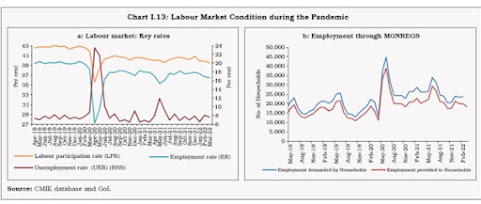

inflation. The following chart from the aforementioned RBI’s Report on Currency

and Finance shows that the unemployment rate in March 2022 was close to 8%. The

CMIE reported that 13 million jobs were lost in June 2022.[viii]

Comparing the conditions in the US and India shows that the situation prevailing in the two economies is quite clearly different. The US economy seems to be operating close to its potential, which is leading to high inflation. On the other hand, India does not seem to be operating close to its potential (as seen by the unemployment rates), and hence its inflation probably requires a different explanation. A simplistic comparison of inflation rates in the two countries (as was done by Subramanian) and then claiming that India is in a much better position is not very helpful.

[ii] Actually,

2% is the target rate of inflation of the Federal Reserve: https://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/economy_14400.htm

[iii] https://www.livemint.com/Home-Page/wBuIFMUxU43ZvJL0443nKP/New-consumer-price-index-to-be-introduced-from-February.html

[v] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Content/PDFs/2SBADRJ060810.pdf

Agree wholeheartedly, Ajit. Two numbers should be on the radar of economists, inflation and output/employment. Never mind that the expected connection between them, the Phillips curve, might not be visible on the screen. The labor market in the US is “tight”. Vacancies are unfilled and increasing wages are on offer. Workers are finding “voice”. Indeed, some observers fear that a wage-price spiral is in the offing. The comparison with India is odious. We are coy with use of the R word but a rising tide of activity to lift the vast and growing informal sector is not spotted.

ReplyDeleteThanks a lot, Romar for your comments. But even the US economy is behaving funnily: 580,000 jobs added but rate of inflation down by half percentage point as per latest numbers. But then one datapoint does not a make trend...

ReplyDeletePrices reflect wage costs and the costs of raw materials and intermediaries. I haven’t considered the latter, Ajit. The causes for them skyrocketing are known, bunged-up supply chains and the war. In theory, these shocks are temporary. Even if the pandemic rages and the war is not called off, there might be reliefs with the lifting of an embargo here, a temporary truce called there.

ReplyDeleteA very insightful piece as always, Ajit. I too agree with the gist of what the CEA has said. I have made a chart of the "distance from inflation target" in the major economies right now. It backs the CEA's point that India is better off on the inflation front. AMP and I were discussing the other day how the US and Europe made an analytical error by responding to multiple supply shocks with a massive demand stimulus. Also, two quick questions. (1) Instead of output gap, which is tricky to estimate for India at the best of times, would it be more useful to look at GDP in FY 22 compared to its pre-pandemic path? (2) Does it make sense to also look at the out-of-fashion Beveridge Curve rather than the PC, as far as the US labour market goes?

ReplyDeleteThanks a lot, Niranjan. I would love to see your charts of "distance from inflation target". Comparing India's inflation with other countries certainly shows India is better off. Form an academic point of view, this is certainly worth investigating. From a more mundane, practical point of view, does this matter for an average Indian consumer? I agree about the output gap and the problems with its measurement. We could compare current GDP with the pre-pandemic path but how do we know how close that was to potential output? In some elementary exercises that I presented at one of the Mumbai Alumni association meetings, I found that post-November 2016, potential output declined quite signficantly. I am not particularly well-versed with the Beveridge curve but Blanchard as a recent piece on this: https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/bad-news-fed-beveridge-space

ReplyDeleteVery Insightfull .

ReplyDeleteAjit, the question you pose can be answered unequivocally. Returning to the comparison with the US, firms claim that prices are hiked because nominal wages are raised. Agitating workers protest that they are doing nothing more than protecting their real wages. The back and forth is familiar from the previous century. Some careful studies have established that real wages in the US are being eroded while monopoly power is being exercised to its fullest. How do Indian income earners compare? While the denominator, the price level, is moving upwards does anyone propose that the numerator, rupee compensation, is rising commensurately? The thesis that the potential level of output is trending downwards is a cause for concern. It suggests the collapse of technological dynamism as well as pessimism about prospects.

ReplyDeleteThat's the problem with analysing how an average Indian consumer is doing. As you said, data on the price level is available with ease, the numerator (earnings) is difficult to get data on, at least with as much frequency as the prices data. As far as potential output is concerned, even the RBI (which I quote) speaks of a large negative output gap post-COVID. I suspect potential output has gone down after demonetisation - one of the earlier Economic Surveys or RBI Reports (don't remember which) also makes a reference to this - of course, without mentioning demonetisation!

ReplyDeleteAjit buddy, you have inspired the following difference between the two countries. American workers give “voice”. Indian workers enjoy the freedom to “exit”. “Loyalty” is unavailable to both.

ReplyDeleteGood one, Romar!!

ReplyDeleteReally informative

ReplyDelete